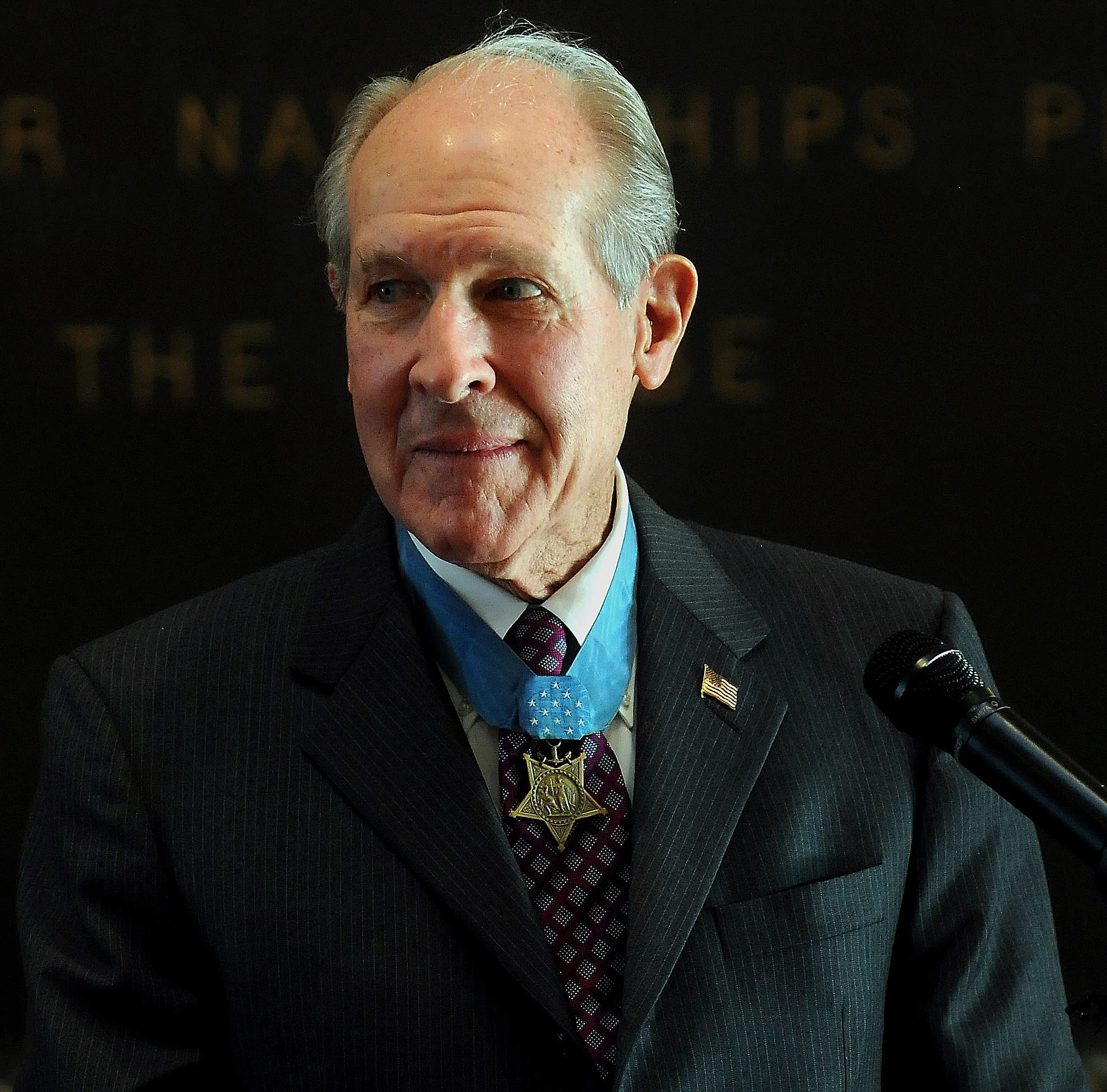

CONVERSATIONS WITH MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENT TOM HUDNER

TOM HUDNER received the Medal of Honor for his actions in an attempt to save the life of his African American wingman Jesse Brown who had crash landed his plane on a desolate mountaintop during the Korean War.

I am posting, for the first time, a transcript of a taped interview about Tom Hudner's reflections on the action and Jesse Brown. The interview took place in Denver in 2007. As an introduction, I have included a brief overview of a conversation we had on the phone a few years ago.

A truly remarkable man.

TOM HUDNER

On March 29, 2014, I called and spoke to Tom Hudner. It was not a formal interview as we had had many of those in years past. He was, as always, soft-spoken, upbeat and engaging. Among the topics discussed was the Medal of Honor Society sponsored Leadership Development Program which has been expanding to schools across the country. Tom was particularly proud of the initiative that brings recipients of the Medal of Honor into schools through personal visits and internet programs.

Tom Hudner, a Korean War veteran, was the first recipient, by date, to receive the MOH after World War II. He remembers at an early inauguration, a duty officer only allowed him one ticket because his guest was not his wife. He said that only happened once and, thereafter, all recipients were invited to the Presidential Inauguration, but had to pay their own way. (The number of living recipients then was perhaps five times greater than the current number of 76 living recipients.)

According to Tom, times have changed significantly. The recipients have been treated with extraordinary respect as they move from city to city for their annual conventions. The last major convention in Chicago was held in 2009 and attended by over 50 heroes.

Tom talked about serving on the policy development committees in the early days of the Medal of Honor Society which was formed in 1958. He has high regard for recent recipients like Sal Giunta, who he had a kinship with since, the oldest recipients he knew at the time had fought in World War I.

2007 CONVERSATION with Medal of Honor Recipient Tom Hudner– Denver, Colorado (This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.)

TOM HUDNER ON JESSE BROWN

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

Ed Tracy: Tell me about your first impressions of Jesse Brown… when you met. Describe who he was, what he was and some of the aspects of what he faced… the struggles he faced and the challenges he overcame.

Tom Hudner: I got my wings in August of 1949 and my first orders were to the Naval Air Station on Long Island. Shortly after I got there, the squadron I joined was decommissioned and I went to another squadron at the same station. It was only when I got my orders to this other squadron did I even hear of Jesse Brown. He had gotten his wings a year before I did but I didn’t know that there were any black naval aviators. When I arrived in the squadron, nothing was said even at that time that Jesse was in the squadron. So, it was a day or two after I got there when I was in the locker room getting ready for a flight when Jesse came in. I wasn’t startled, but I was a little bit surprised. He was very quiet. He just introduced himself. “I’m Jess Brown.” Very low key. We had a few words that I really don’t remember and then I went out to the flight.

Of course, as in squadron life, we’d see each other on a daily basis. It was obvious from the very beginning that he was very well liked by everybody, but there was no deference in any way. He was just one of the guys. No thought whatsoever that he was black.

ET: Would you describe him?

TH: Well, as I remember he was probably about five ten or five eleven. Slender fellow. He was a track man so he looked like a sprinter. With a ready smile. He had a great sense of humor. He was the butt of a lot of jokes, and he joked about a lot of other people, too. I wouldn’t say that he was anybody special in the squadron except that not everybody was proud of the fact that he was there. Frankly, what made it better was he was a helluva good guy.

He was an ensign. He’d been an ensign for… I don’t think he’d been an ensign for a full year, so he was one of the lowest seniority guys in the squadron. He was given the responsibilities of a young officer in his position… as the Navy emphasized, you did small jobs to increasing responsibility as time and rank goes on. He didn’t get his work done on a number of times, no more than anybody else, so the squadron CO would have to kick his butt to get his paperwork done and things like that. But he didn’t experience anything that the rest of us didn’t experience.

DATING AND MARRIAGE

TH: How long he was dating his future wife, Daisy, I don’t know, but apparently they had been dating quite a bit. So, when he got into the flight program, he got in as a non-officer and the Navy would not take married non-officers. As an officer, you could go through the program married. But, as a non-officer, you couldn’t.

He ran into the typical problems that blacks faced at the time. Being down there in the south, especially Pensacola, no matter where he turned, he was given a hard time by people. The fact that he was a Naval aviation cadet didn’t deter a lot of these people from saying anything. He experienced harassment a number of times while in uniform by shore patrol and others.

The flight program was demanding. He started in 1947, got his wings in 1948. There was a lot of pressure on students at that time.

I don’t think his girlfriend, who came from Hattiesburg, could afford to come and see him at all. Whenever he had leave and did have a chance he drove back from Penscaola to Hattiesburg to see her. I don’t know how long a drive that would be but not too much effort.

He was under so much pressure. He finally married Daisy while he was in the training program, which was very definitely against regulations. But she, of course, gave him much comfort and solace. I’m sure that he attributed being with her as an anchor.

Jesse and I were not very close. He was an Ensign and I was a LTJG. At that time, there was a big difference between an Ensign and everybody else. He had very good friends who were my rank and were true friends. The difference, though considered minor, was a big one at the time.

Also, I was Naval Academy and had several Naval Academy friends before coming in there and these other fellows, they were our friends too, but I gravitated toward those I knew before. So, that is why I didn’t see Jesse more than I did. Plus, the fact that I was a bachelor and a couple of these friends were bachelors, too. We just didn’t mix at all.

ON THE MOUNTAIN

ET: Take us through Jesse’s crash and what you saw from above.

TH: In those days, for all takeoffs and landings your canopy was open. The canopy would slide back and forth on rails. When it was open, there was a little latch that would flip over onto the track. So, if you made a sudden stop, it would keep the canopy from going forward.

When he landed and the canopy was open, I presumed he had latched it open… it latches open automatically. But he hit with such force, that the canopy shut. So, we couldn’t see him in the cockpit. As soon as this happened, the flight commander left us to climb to a higher altitude, because this is a mountainous terrain… and to call for assistance presumably from the Marines because they were known to have helicopters in the area. So, several of us… three or four, so some other aircraft from other flights, came over for curiosity or however they could help.

Then someone said, “He’s waving at us.” Jess had managed to open the canopy… and we could see him. He was waving at us to let us know that he was alive. The flight commander came back on our frequency and said that helicopters were on the way. I don’t know when it was said, but it would be as long as a half an hour before they could be there. In the meantime, smoke was coming out of the cowling back along the fuselage. That’s when I thought by the time he gets here the smoke could turn into flames.

Our flight leader was still not on our channel, so I don’t think I even called for permission to go in. I just… when the time came, I just said “I’m going in.”

ET: He wouldn’t have given you permission to go in anyway…

TH: No.

ET: Was there any buzz on the radio after you made the decision to go in?

TH: I don’t remember any comments on the radio. There may have been some, but I don’t remember any. It was not at all negative on the frequency. I don’t know how many were on at the time, but no one said “Don’t do it.” So, I’ve always said, no one told me not to.

AT THE CRASH SITE

ET: So Jesse is out of his gloves and parachute. He has been trying to get out of the cockpit on his own. His hands are frozen. What are the conditions?

TH: There is about twenty inches of snow on the ground. Not constant, but it was knee high. The weather was clear. I don’t remember there being much wind at all but it was cold.

I had a blue knit cap that sailors wear. They call them Watch caps. I used to carry one of those in my flight suit in case I got stuck. He had taken his helmet off and that was on the floor of the cockpit. So, I pulled the watch cap over his head and I had a white Navy scarf and wrapped that around his hands but it didn’t do much good since his hands were so frozen.

The fire subsided. Hydraulic fluid or possible oil dripped on the hot pipes and plumbing that went up through into that part of the airplane. It diminished as time went on. There was almost no wind, but what wind there was blowing the smoke back up the fuselage but not into the cockpit. I was waiting for the helicopter. Frankly, for lack of anything better to do, I was throwing snow on the fuselage, under the cowling, which did almost no good.

ET: Do you recall Jesse saying anything about Daisy at this time?

TH: One of the few things he said to me… he just said, “If anything happens to me, just tell Daisy how much I love her.” There was no time for small talk, so we didn’t talk.

ET: How soon did the helicopter come?

TH: It was about a half an hour. The helicopter pilot got the word that there was a plane down. The helicopter was an Sikorsky H03. There are pictures of them. One of the smallest. Not a bubble canopy, but spheroid. A lot of glass or plastic in the front of it. Maximum capacity was 3: pilot, copilot and crewman. The pilot took off with a crewman to help get Jesse out of the cockpit. When he heard afterwards that there were two of us on the ground, he had to turn around and go back and let the crewmen off. He was going in there all by himself. He didn’t know what the circumstances were. The planes went down is about all he knew.

ET: So, that trip back took even more time for him to get there.

TH: Oh yes. That had to add at least fifteen minutes to it. I don’t know if I told you this, but when we left Norfolk, VA on the way over to Korea, the day we got underway, we went up on deck, there are six helicopters there with a Marine detachment , so there were 10 pilots and supportive enlisted personnel. We took them all to Korea from there which was the better part of two weeks. We left the first of September and didn’t have our first flight until the 10th of October.

These Marines were riders. They couldn’t fly well and ward room. When you go through several time zones no one can sleep. We still had our work to do but these guys didn’t… what I’m leading up to is that after being on the ship for the better part of a month, the rescue pilot came and saw the only black face in naval aviation in the cockpit. I don’t recall if he said anything to Jesse. Jesse was comatose at the time. In and out of consciousness. He was very calm, but we think that he was in shock. I sometimes wonder how he could have been talking at all.

ET: Was he saying anything that made sense?

TH: I don’t remember that he did. There was so little conversation between the two of us. I didn’t spend much time in the cockpit. It was difficult. Very hard to get up there. I went back to my plane to give a status report. My radio was still working. Some said I shouldn’t have turned it off but I conserved the batteries so the radio would work longer.

ET: Were there enemy patrols in the area?

TH: I am told by some who were flying in the area that there were, but they were not close and I saw no evidence except a single set of footprints… tracks in the snow. The snow and getting up a couple of times to check on Jessie is all that I did. I was just trying to encourage him to stay long enough to help Jessie. Jessie said virtually nothing while Charlie and I were trying to figure out what to do… in the back of our minds, I think, knowing there is nothing we can do.

ET: Once the axe comes out… you can’t chop steel with an axe.

TH: Charlie was naïve just asking for an axe.

ET: So, at one point Charlie looks at you and says, “Tom it’s getting dark.”

TH: Charlie turns to me and says, “Tom, it’s getting dark and I can’t fly… I don’t have the instruments to fly at night. I’m going. It’s up to you what you want to do, but I’ve got to get outta here.” It wasn’t a matter of being chicken or anything… it was just the reality. Frankly, Jesse may have been dead at the time he said it. I said we don’t have the equipment to get you out of here. We’re going back to get something. I don’t know… he didn’t say anything but I don’t know if he even heard what I said to him. My only hope is that…looking back on it, that he knew he wasn’t alone at the time he passed. No matter what the circumstances, we don’t want to be alone at that time.

ET: I know how difficult this is to bring back. I cannot tell you how much I appreciate the time you’ve spent today talking about this.

TH: Jess got his wings just about the time that President Truman issued the executive order to desegregate the Armed Services. The Navy had the reputation of being the most segregated due to the particular nature of the Navy. The posts aboard ship. Not being able to get away. He came into the Navy on active duty as an officer into a recently desegregated Navy. Just because of the proclamation, the Executive Order, didn’t mean that anybody felt any differently about it It isn’t that he ran around the ship and said “…because of this executive order you have to treat me differently.” He wasn’t that way at all.

Jesse was somebody that showed right from the day we met his reticence to force himself… or break anybody’s personal zone. He didn’t even offer to shake hands at first. He didn’t want anybody to say that they didn’t want to shake hands with him. He was very respectful. He didn’t have any attitude, hauntiness, subservience. He was just one of the guys. Just from his attitude again, everybody did truly like him.

I ran into people years later who were in the squadron before I got there who spoke very admiringly of Jesse. It was pretty obvious that if he had stayed in the Navy, which I do not believe were his intentions, he’d have been a leader. Whether he would have been the first black Admiral, I don’t know.

He was a decent person. He could have been a son-of-a-bitch to the stewards and the others, but he wasn’t. The stewards hovered around him which is a very natural reaction. I don’t think he went out of his way… never got friendly with enlisted personnel. He was an officer.

Although Jesse was only an Ensign, because of his breaking through this big, big barrier to become a Navy aviator, he was really a role model. Everyone respected him and he was certainly headed for better things. He was accepted at Ohio State University. After he served his time, his intentions were to become an engineer or maybe even an architect. Whatever, he’d have done, he would have been fine.

ET: When you returned, what was the mood back on the ship knowing that Jess was gone?

TH: There was a big void. He wasn’t just one of the guys who happened to fit in. He’s the type of guy, not to dramatize it, but lights would shine when Jesse came in. He was not a back slapper either. He’d come in unobtrusively. He’d play acey deucey with a lot of the guys. He was well liked.

Before we deployed, he had a hard time as a new Naval aviator with a new wife. He couldn’t find any housing. I’m guessing that he looked up to fifteen miles away for a house or room to rent and everyone said just missed it or too late. There was a black enlisted man pay officer who somewhat befriended him. He found a place for him near Providence. So, it was not just a few miles off the base. He had to go that far up. In the non- segregated New England. Think about what it would have been anywhere in the South.

But he was philosophical about it. A lot of the new squadron mates were helpful to him, but there was a limit to what they could do, too.

I was always a little disappointed that the Navy didn’t make more of Jesse Brown. There was such an emphasis on bringing blacks in. If Jesse had been just an ordinary guy who got caught in something, but he was a guy at a very low level rank wise who was an inspiration, not only to the other blacks but everyone who knew about him. But, they didn’t do more about it.

Throughout my career, I always heard about the Tuskegee Airmen, but I learned that there were more than one Tuskegee Airmen and Jesse was just one guy. As I met some of them, they had never heard of Jesse Brown.

I think the word is getting around. Part of the heritage of the naval aviators is the story of Jesse Brown.

www.conversationswithedtracy.com